![]()

Dr. Gene Kerns, Chief Academic Officer, Renaissance

Meet the Reengage Students Strand

While multiple reports document the impact of the global pandemic, we have failed to examine decades of sustained, perhaps exponential, loss of learning opportunity in reading and mathematics. As schools across the nation shut down, so did, through no choice of their own, did learners. Bellwether education estimates 3 million students have yet to return to school, whether in person, on-line, or in a hybrid model. This nation must restore the promise of 3,000,000 students—not only in reenrolling them in school, but in fully reengaging them in their own learning.

Request for articles:

The following article specifically address reengaging at-promise learners as the primary decision maker for their own learning. Further, this article lists specific evidence-based instructional techniques and resources to reengage learners. We invite you to share your expertise in reengaging at-promise learners. See the Journal Submission Form to access submissions guidelines and submit your article for consideration.

Inform Learning

For those looking to increase student achievement, formative assessment holds tremendous potential. Wiliam (2011) asserts that “the currently available evidence suggests that there is nothing else remotely affordable that is likely to have such a large effect” as focusing on formative assessment classroom strategies. Similarly, Stiggins (2014) proclaims “assessment . . . may offer more promise for prompting learner success than any other instructional practice or school improvement innovation we have at our disposal” (Stiggins, 2014, pg. 4). Clearly, this is an area that warrants deep exploration.

First, let me share an excellent resource for formative classroom strategies. My favorite book is Embedded Formative Assessment by Dylan Wiliam. I like the text because it’s a rather compact read and, more importantly, it contains 53 different formative classroom strategies. I’ve used it during keynotes, conference presentations, and onsite training and it’s always a hit with teachers as teachers love strategies that they can put into use easily.

While tools, strategies, and even tests of nearly any form can be used formatively, for our purposes here it is most appropriate to focus on strategies used by teachers while learning is occurring. The purpose is not to rank or rate students, the purpose is to inform learning. This is the area of primary focus for Dylan Wiliam, Paul Black, Rick Stiggins, and the other authors who focus in this area with Black and Wiliam (1998) defining formative assessment as “activities undertaken by the teachers and/or by their students, which provide information to be used as feedback to modify the teaching and learning activities in which they are engaged” (p. 142 – emphasis added).

For example, both Wiliam and Stiggins suggest that prior to working any major assignment students should be given some work samples and asked to rate them in terms of quality. This is critically important at points when we ask students to produce forms of work that may be utterly foreign to them. Most students had never seen a lab report when their science teacher called upon them to write one. Few students have read research papers before writing one or been to a science fair before crafting a science project. In short, “Low achievement is often the result of students failing to understand what is expected of them” (Black & Wiliam, 1998). We must ensure that prior to beginning work on major projects that students clearly understand what is expected of them.

By asking students to rate the work samples, using a rubric where appropriate, we can gather some tremendously useful information. If they are able to rate correctly – tell you which work samples are the best and which are lacking – this is an excellent sign that they are ready to produce work on their own. If they are unable to rate work samples correctly, it would be unwise and frustrating to ask students to being working on their own projects. If students cannot see or perceive the lack quality in someone else’s work,

When students are unable to rate samples correctly, teachers must focus in on their discussions of the work samples for the insights that those discussions can offer. What do the lower quality work samples lack, or the best samples contain, that students fail to see? Listening closely to these discussions will inform our practice and help us know what we need to teach our students to see.

Learning about useful strategies is a straightforward thing. As such, we need not dive deeply into more strategies here. I do, however, want to offer a higher-level insight, one that is particularly powerful for those of us who serve at-promise students. This insight has to do with the potential of formative assessment to tap into deep motivational forces that can foster prolonged engagement on the part of students.

In their work, Rick Stiggins and his colleagues at the Assessment Training Institute, most notably Judi Arter, Jan Chappuis, and Steve Chappuis, give “student motivation” particular emphasis, noting formative assessment’s potential to provide feedback that can powerfully engage students. They feel that this consideration is critical as “powerful roadblocks to learning can arise from the very process of assessing and evaluating . . . depending on how the learner interprets what is happening to him or her” (Stiggins, 2014, pg.17) “Traditional testing practices in the United States . . . cause many students to give up in hopelessness and accept failure rather than driving them enthusiastically toward academic success” (Stiggins, 2014, pg. 3).

In seeking to illustrate how formative assessment can meet essential motivational needs, Chappuis (2009) drew insight the work of Australian psychology professor Royce Sadler (2002) who asserts that if you want students to be deeply motivated and to be able to sustain that motivation, they must always be able to answer the following three questions:

- Where am I going? What is the expectation of me?

- Where am I now in relation to that expectation?

- How can I close the gap?

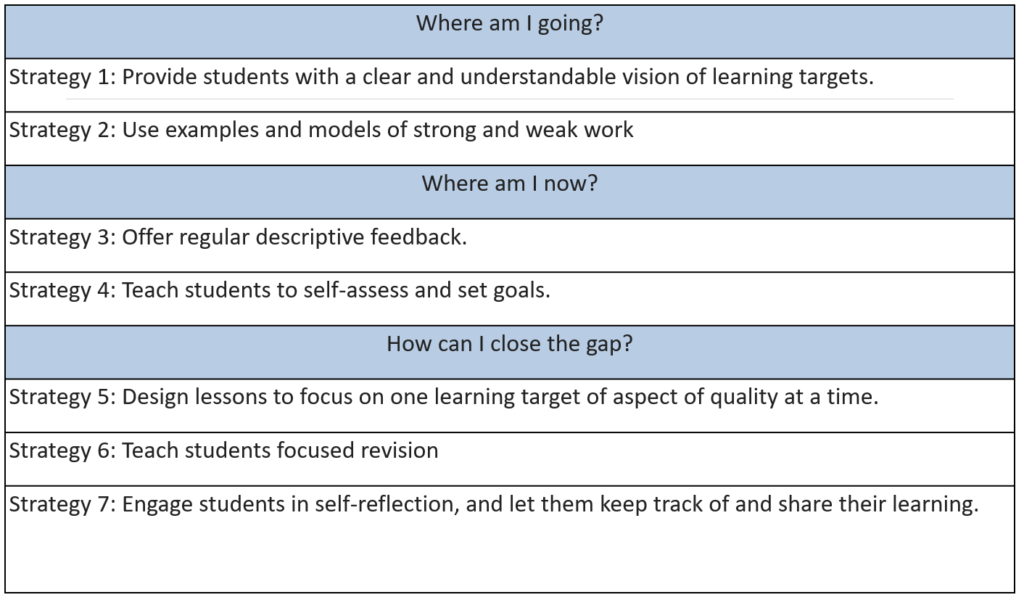

To illustrate the potential power of formative assessment strategies and processes to answer these questions, Chappuis (2009) then organized the common formative assessment strategies of “assessment for learning” under the headings of the three essential questions as outlined in Figure 1 (Chappuis, 2009). The result is a clear illustration of how motivation is driven through formative assessment practices, “focusing on the student as the most influential decision maker in your classroom” (Chappuis, 2009, pg. 11).

For Rick Stiggins, exploring the power of assessment strategies to motivate students isn’t just a professional interest, it is deeply personal. In a recent book, Stiggins described his own K-12 schooling as a period where he had little faith in his abilities. Things change drastically, however, when he entered the Air Force where he experienced an assessment process that was completely different and that provided him the answers to the essential questions of where he was going, where he was in reference to that, and how to close the gap between those two places. In the following narrative, Rick describes his transition from struggling student to empowered learner:

Poor early performance in reading aloud devolved into unfortunate personal generalizations about my overall academic ability and, ultimately, into a record of chronic low performance. In my mind I came to see failure as inevitable, and I gave up. To my mind, I had no way of controlling or even influencing my own well-being in school. Ultimately, because I failed to learn to read, I experienced low performance in most other academic contexts for a long time. As you can see, I generalized my inference that I was not a good student and never would be.

Once I had given up in the early grades, the underlying truth of my learning potential no longer mattered. Even though I found out later that my elementary records included a pretty high IQ score, my actual intellectual capabilities became irrelevant. It didn't matter what my teachers believed about me. It didn't matter that my mom had confidence that I could succeed if I just tried. One of my teachers noted on one report card, “Rick seems to have a mental block to reading.” Indeed.

When small measures of learning success finally began to emerge much later in Air Force tech school, my emerging confidence fueled little bits of cautious optimism they gave me the inner reserves needed to risk trying again -- and this time, with a bit more energy. The result was more success, and with that success came a growing sense of internal control over my own academic well-being. Like most winning streaks, mine took on a life of its own. I entered a personal upward spiral that left my unhappy history of failure far back in the dust.

I share this analysis of my failure and success, of pessimism turned to optimism, in order to point out the powerful roadblocks to learning can arise from the very process of assessing and evaluating the performance of the learner, depending upon how the learner interprets what is happening to him or her.

Stiggins (2014, pg. 27)

Merchants of Hope

Stiggins passionately and eloquently states that “teachers must be merchants of hope” (2014, pg. 45). Coming to better understand both individual formative assessment strategies and how they can collectively provide powerful motivational insight to students allow us to offer hope to students who are, indeed, the most important consumers of assessment information in all of education.

References

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. Phi Delta Kappan, 80(2), 139–148.

Chappuis, Jan. Seven Strategies of Assessment for Learning. Boston: Pearson, 2009.

Stiggins, R. (2014). Revolutionize Assessment. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Wiliam, D. (2011). Embedded formative assessment. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree.