The Terrain of CTE

In various regions, Career Technical Education (CTE) or Career Education (CE) represents a sophisticated integration of academic and industrial principles. CTE extends its influence from creating collegiate-level degrees to establishing programs in grades 7-12. These programs are strategically designed to align with industry requirements, equipping students with indispensable skills for the job market. To stay attuned to industry needs, CTE divisions must maintain a constant awareness of the regional economy and labor market dynamics (Congressional Research Service, 2022).

This discussion aims not to delve deeply into the political intricacies of CTE or Education codes but rather to navigate the current educational landscape. Together, we seek to comprehend the challenges we face in the classroom and our pursuit of supporting student completion and success. When students encounter difficulties, it's not a reflection of the educators' commitment or competence but rather a testament to the complexity inherent in CTE, which we’ll dive into for a moment. Elmore (2008) has written extensively about this, and his introduction of the instructional core beautifully emphasizes the student, the content, and the teacher. For a moment, though, we will discuss from a slightly different angle. On the structural side, we have the CTE framework, which requires academic institutions to engage regularly with the industry (U.S. Department of Education, n.d.). This is critical in ensuring our students are well-equipped to enter the workforce. When an industry has employees who need to understand spreadsheets, CTE instructors have to be ready to pivot to ensure those skills are integrated into our classes; when local employers are struggling with employees who have weak cultural and social/emotional intelligence, CTE has to start integrating those skills in at an earlier stage. Updates in federal or state requirements for disciplines like welding demand agility from CTE administrators, curriculum developers, and instructors. Each facet necessitates flexibility, data-informed decision-making, and deep connections within the regional community.

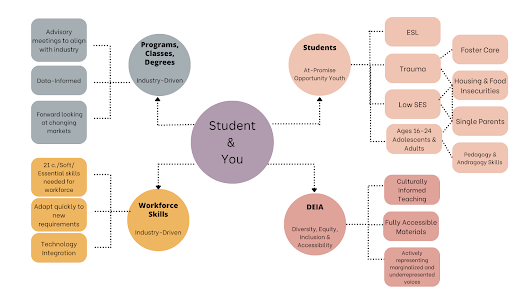

On the classroom side, we encounter classroom best practices framed within the DEIA framework – Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility (Aschenbach, Cheryl, 2022; California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office, 2021; Lynn, M., 2022). Well-equipped instructors adopt culturally informed teaching methods, intentionally include the voices of minority groups and underrepresented peoples within the classroom, and ensure all materials are accessible for individuals with various disabilities. On the student side, engaging at-promise or opportunity youth students (aged approximately 16 to 24) means the instructor is working with both students who are developmentally and cognitively adolescents and those who are well within the adult range. This requires instructors to balance pedagogical and andragogical (adult learning) skills adeptly. By definition, at promise or opportunity youth students are disconnected from education and/or employment, bringing unique challenges such as trauma, low socioeconomic status, single parenthood, and housing and food insecurities. All of these components swirl around instructors as we work to create a classroom where learning needs to be optimized. Faculty are often at a loss when students struggle, not because of lack of skill, competency, or care. Still, because so many factors are pressing in, we often don’t know where to start our troubleshooting. Figure 1, represents an informal mind map created by CTE student support services and faculty when considering the areas of impact on students.

Figure 1. Outside Influence and Student Engagement

While this list is far from comprehensive, it illustrates briefly the web of complexity within which faculty, staff, and administration function.

The essence of this conversation is to introduce the significance of professional learning networks and an educational framework to assist those who engage with students in navigating the myriad challenges in their spaces.

What This Means for You

First, I want to say that you are seen! When students are disconnected and struggle with succeeding, it can be daunting to know where to begin. Examining each step in its sphere can feel less overwhelming (or more so) once you realize how many areas of influence there are. Professional learning networks provide a space to engage with those in the trenches with you, to learn what others are doing, and to create a community that isn’t afraid to be curious, empathetic, innovate, and, yes, even to fail.

Professional Learning Networks

Educational professional learning communities (PLC) is a practice that has a positive impact on education when implemented correctly. Unlike PLCs, which are focused on one school, Professional Learning Networks (PLNs) remove that barrier and reach across the aisles across schools across districts, and in some spaces, across countries. Professional Learning Networks are defined (Poortman and Brown, 2008; Prenger, R. et al., 2021) “as any group who engage in collaborative learning with others outside of their everyday community of practice, in order to improve teaching and learning in their school(s) and/or the school system more widely.” Being a part of a network for individuals like yourself who are working to the same end as you, re-engaging individuals disconnected from education and employment, and working to support students as they strive for the economic stability that comes from increased educational attainment. While we are all working towards the same objectives, the barriers we experience along the way likely vary in nuances but carry deep similarities in their core. These networks are valuable because they generally focus on best practices in teaching, identifying what is most impactful in student retention, completion, and success, and how the impacts of factors outside of school, as briefly addressed above, can be strengthened to support the student or mitigated to lessen the force working against the student. To this end, one learning framework will be discussed here in the hopes that it can stir conversation and curiosity among you, your peers, and your future (or current) Professional Learning Network.

Positive Youth Development (PYD) Framework

Growing up, my parents always reminded me,

Watch your thoughts, they become words.

Watch your words; they become actions.

Watch your actions; they become habits.

Watch your habits; they become character.

Watch your character; it becomes your destiny.

While we may read this and nod our heads in agreement generically, the reality is the way we view the world and how we understand those around us greatly impacts how we engage with students. While this quote is an important reminder that the same things can have a great impact on our future, the better choice is to choose a destiny and work backward to determine what habits and actions will be required to achieve that destiny. Choosing to intentionally pursue a framework such as Positive Youth Development (PYD) (Cornell, University, n.d.; Olenik, Christina, 2019;). sets us on a specific path. Choosing not to engage intentionally puts us in a position where we can be more reactive instead of proactive.

The Interagency Working Group on Youth Programs defines PYD as, “an intentional, pro-social approach that engages youth within their communities, schools, organizations, peer groups, and families in a manner that is productive and constructive; recognizes, utilizes, and enhances young people’s strengths; and promotes positive outcomes for young people by providing opportunities, fostering positive relationships, and furnishing the support needed to build on their leadership strengths” (Positive Youth Development, n.d.). While the employment of the PYD framework is generally on a larger scale, its core principles have application in every student interaction. There are eight outlined integration norms (Integrating Positive Youth Development into Programs, n.d.)

-

- Physical and Psychological Safety

- Appropriate Structure

- Supportive Relationships

- Opportunities to Belong

- Positive Social Norms

- Opportunities to Make a Difference

- Opportunities for Skill Development

- Integration of Family, School, and Community Efforts

The important difference between PYD and other adolescent frameworks is that it does not approach interactions with at-promise or opportunity youth from an intervention standpoint. It does not look at what they are doing wrong and tries to address how to make it right, like teen pregnancy or drug abuse. Instead, it requires us to look for strengths already possessed by the student and directs us to call out and nurture these assets. Additionally, this framework is not something DONE TO students. It is a framework engaged WITH students. Students are partners with their teachers, community, and friends. The student's voice is paramount in creating programs, classes, activities, and direction.

As we consider our programs, classes, assignments, and assessments, what would it look like to function within a framework where individuals who have been disconnected from employment and education are partners with us? What methods could we employ to ensure the student voice is intentionally sought? While we will dive deeper in the coming months on learning theories and tools through professional development and professional growth opportunities with RAPSA, I encourage you to consider reviewing the list above. Which components do you currently do well? Which are you unsure about, and which would you need support implementing? Depending on the role you have in the student journey, your answers will vary greatly, but discussing this with colleagues in your area, folks in other areas of the student journey, or even your colleagues in other schools, is a wonderful way to foster a network of curiosity, empathy, creativity, and innovation!

Dr. Elisa Queenan is a Career Technical Education, Business, and Economics professor at Porterville Community College.

References

Aschenbach, Cheryl. ASCCC Secretary (2022, April). DEIA competencies and criteria: Defining equity-focused practitioners in the California Community Colleges. ASCCC. https://asccc.org/content/deia-competencies-and-criteria-defining-equity-focused-practitioners-california-community

California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office. (2021). DEIA Competencies and Criteria. https://go.boarddocs.com/ca/cccchan/Board.nsf/files/C8FVAS7FD746/$file/dei-competencies-criteria-a11y.pdf

Congressional Research Service (2022, April 15). Strengthening Career and Technical Education for the 21st Century Act (Perkins V): A Primer. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47071

Cornell University. (n.d.). Positive Youth Development Resource Manual. https://ecommons.cornell.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/291c2b13-679a-4735-9b81-1da1ea55a0dc/content

Doğan, S., & Adams, A. (2018). Effect of professional learning communities on teachers and students: Reporting updated results and raising questions about research design. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 29(4), 634–659.

Elmore, R. F. (2008, June). Improving The Instructional Core. Achieve the Core. https://achievethecore.org/content/upload/Improving%20The%20Instructional%20Core_Elmore%20Article.pdf

Lai, M. K., & McNaughton, S. (2016). The impact of data use professional development on student achievement. Teaching and Teacher Education, 60, 434–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.07.005.

Lomos, C., Hofman, R. H., & Bosker, R. J. (2011). Professional communities and student achievement—A meta-analysis. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 22(2), 121–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2010.550467.

Lynn, M. (2022, December 29). The current state of Diversity, equity, and inclusion in K–12 public schools. Hanover Research. https://www.hanoverresearch.com/reports-and-briefs/the-current-state-of-diversity-equity-and-inclusion-in-k-12-public-schools/?org=k-12-education

Olenik, Christina. (2019). The Evolution of Positive Youth Development as a Key

International Development Approach. Global Social Welfare: Research, Policy & Practice., 6(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40609-018-0120-1

Poortman, C. L., & Brown, C. (2018). The importance of professional learning networks. InNetworks for learning (pp. 10–19). Routledge.

Positive youth development. Positive Youth Development | Youth.gov. (n.d.). https://youth.gov/youth-topics/positive-youth-development

Integrating Positive Youth Development into Programs. Positive Youth Development |

Youth.gov. (n.d.). https://youth.gov/youth-topics/integrating-positive-youth-development-programs

Prenger, R., Poortman, C.L. & Handelzalts, A. Professional learning networks: From teacher learning to school improvement? J Educ Change 22, 13–52 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-020-09383-2

Stoll, L. (2015). Using evidence, learning and the role of professional learning communities. In C. Brown (Ed.), Leading the use of research and evidence in schools (pp. 54–65). London: IOE Press.

U.S. Department of Education. (n.d.). Insights into how CTE can improve students’ income after they graduate. CTE Data Story. https://www2.ed.gov/datastory/cte/index.html