![]()

Dr. Gene Kerns, Chief Academic Officer

Meet the Knowledge, Vocabulary, and Equity Strand

Educational journalist, Emily Hanford, states that “equity in education begins with early decoding skills.” Indeed, for most learners, mastering the mechanics of a sound-based language, is the pathway to literacy; however, once these mechanics are developed, reading growth depends, more than anything else, on each reader’s vocabulary and background knowledge. We invite you the ponder equitable access to literacy acquisition and share your thinking via future articles in this strand.

Request for articles in the Knowledge, Vocabulary, and Equity Strand

Request for articles within the Knowledge, Vocabulary, and Equity strand—should reflect the critical importance of building a vast repertoire of knowledge, and an exceptionally deep vocabulary. Articles regarding best practices in digital reading would add depth to this strand. See the Journal Submission Form to access submissions guidelines and submit your article for consideration.

The Soul of Learning

In ensuring that the promise of all students is developed, our attention often focuses on literacy. This is quite appropriate. As Schmoker (2018) notes, “intensive amounts of reading and writing are the soul of learning” and while “all disciplines connect and contribute to success in other disciplines… language competency is the foundation of learning.” While we have long understood the primacy of literacy, it is painfully clear that for many intents and purposes, we do not clearly understand how promote the optimal development of literacy.

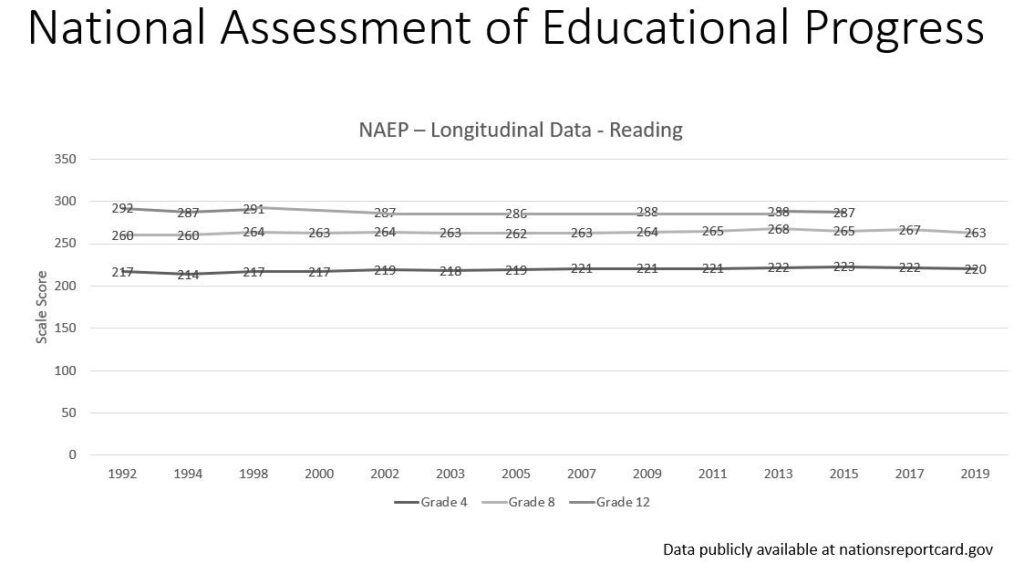

Consider the results from the National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP). Flatlined scores go back decades and have remained flat despite the increased accountability of No Child Left Behind, the resulting changes to many school schedules that took time from all areas other than ELA and Math to increase time for these areas, and billions of dollars pumped into early grades reading instruction through Reading First. We have made massive investments, and those investment simply are not producing returns.

Of all the investments we have made in literacy that haven’t paid returns, the most telling may be the increased time allocated to English Language Arts IELA) at the cost of other content areas. Most school schedules post-NCLB differ radically from those pre-NCLB. McMurrer (2007) notes there was a “47 percent reduction in class time devoted to subjects beyond math and reading” in response to NCLB (as cited in Hirsch, 2018, p. 61). Consider what the investments of additional time mean. By allocating more time to ELA, we were essentially saying “We know exactly what to do to increase literacy proficiency, we just need some more time to do it.” We unquestionably got more time, but we have little to nothing to show for it. We must not have known what to do after all.

This brings to mind the familiar definition of insanity often attributed to Albert Einstein but actually written by novelist Rita Mae Brown (1983)—doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results. It is very clear that there are problems with our current approach to literacy and continue to do the same thing will not result in a different result for at-promise students. According to James “Lynn” Woodworth Commissioner National Center for Educational Statistics because, if one disaggregates the flatlined overall data, it’s shocking to see that “the bottom is dropping at an alarming rate.”

This problem is complex and there are multiple contributing factors. Given that time and space considerations here are limited, we will only address one contributing element, the role of background knowledge in reading comprehension. Pimentel (2018) refers to research in this area as “some of the most profoundly important, yet under-recognized, reading research” available and asserts that “the implications for literacy instruction are enormous.”

While we have always, on some level, acknowledged the role of background knowledge in reading comprehension, we rarely understood the scale of knowledge’s impact. A wave of modern research has clearly documented this. A lack of background knowledge can stimy the comprehension of even the most proficient readers, and when background knowledge is controlled for, gaps in reading performance which typically follow socio-economic levels, disappear.

This is because, as Willingham (2017) notes, “Writers always omit a great deal of information needed to make sense of what they write” (p. 116). If writers could not assume readers have a general knowledge base that is “a million miles wide, but just a few inches deep,” then their writing would have to be unwieldy and boring (Willingham, 2017, p. 118). There are names, dates, places, and concepts that they automatically assume a reader will understand (e.g., “That’s a trojan horse.” “They reacted like Pavlov’s dogs.” “You’re charging at windmills.”) These examples, and countless others, come from art, music, history, science – so much of the content that we cut to create more time for ELA and math.

Consider a recent study done by Adam Tyner and Sarah Kabourek with the Fordham Institute, viewed by some as one of the most significant pieces of educational research of 2020. In the study, groups of students received additional time in varying ways with the goal of increasing reading proficiency. One group, for example, received more time with reading strategy instruction. Another group received more time with social studies. Somewhat counterintuitively, the researchers found that “Literacy gains are more likely to materialize when students spend more time learning social studies.” Yet, in a misguided attempt to raise reading scores, we cut time from the social studies; the very content proven to raise reading scores.

Hirsch (2018) asserts that “knowledge is by far the most promising avenue to carry us out of the reading slump we are in” and “is by far the most promising way to advance reading skill for all” (p. 31). He adds that schools should come to the realization that “the secret to answering [the complex questions of today’s high-stakes tests] will not be hours of practice of ‘inferencing skills’ and ‘close reading skills,’ but can only be answered through the student’s prior relevant knowledge of the words and the topics. (Hirsch, 2018, p. 30)

Willingham (2017) speaks directly to the needs of at-promise students when he advances that background knowledge is a primary cause of flatlining reading scores specifically noting that “students from disadvantaged backgrounds show a characteristic pattern of reading achievement in school; they make good progress until around fourth grade, and then suddenly fall behind. The importance of background knowledge to comprehension gives us insight into this phenomenon” (p. 128).

In other words, while many students effectively learn the foundational reading skills in the early grades (as attested to by higher proficiency rates at early grade where foundational skills are the focus of those tests), gaps in performance widen quickly in the later grades. This is not because of any reading skills deficiency, but rather a lack of background knowledge. These gaps become apparent when success on later grades tests requires not only foundational reading skills, but also a broad base of general knowledge.

This insight has huge implications for how we address the literacy needs of all students, but at-promise students in particular. When student appear to struggle with reading, we commonly focus on reading comprehension strategies. While there is a definitive research base on the efficacy of such strategies, what most fail to realize is that such strategies “are quickly learned and don’t require a lot of practice” (Willingham and Lovette, 2014). Multiple studies have documented that, after a handful of lessons on any strategy, students have received all possible benefit. “Ten sessions yield the same benefit as fifty sessions” meaning that “instruction [on strategies] should be explicit and brief” (Willingham and Lovette, 2014).

“When it comes to improving reading comprehension, strategy instruction may have an upper limit, but building background knowledge does not; the more students know, the broader the range of texts they can comprehend” (Willingham and Lovette, 2014 – emphasis added). The following section from Literacy Reframed speaks to this dynamic through the lens of “The Matthew Effect”:

Addressing the need for knowledge will significantly help teachers address persistent achievement gaps. Many discussions about such gaps reference the Matthew effect. This concept is based on the following Bible verse: “For whosoever hath, to him shall be given, and he shall have more abundance: but whosoever hath not, from him shall be taken away even that he hath” (Matthew 13:12, King James Version). Loosely paraphrased, this verse is familiar to many as the aphorism, “The rich get richer, and the poor get poorer.” When we understand the role of knowledge in comprehension, the Matthew effect applies perfectly: readers with a lot of knowledge become even better readers, and readers who lack knowledge fall further and further behind.

Some students come to school rich in knowledge. Before they could read, they were read to. Once they could read, they were encouraged and supported in doing so. They have visited museums and historical sites, and they have traveled to other cities, other states, or even other countries. Because of the knowledge they have, they take away more from every school lesson, lecture, video, field trip, or other educational experience than their classmates do. As Hirsch (2018) remarks, “The early knowledge base that has been gained by fortunate students is like Velcro; it is a base to which further knowledge sticks more readily” (p. 164). They are rich, and they get richer.

In contrast, other students come to school poor in knowledge. They were seldom, if ever, read to and might not even have a single book. Their home conditions or the responsibilities they bear (such as helping care for younger siblings) are not conducive to wide independent reading, and if they do have the time and inclination to read, they may have few books on hand. They have rarely left their immediate neighborhoods or towns, so their world concept is limited. As a result, they take away far less from the same educational experiences that their rich-in-knowledge classmates thrive on. They can be sitting in the same classroom, and while the knowledge-rich classmates beside them get richer, they fall further behind.

So, what does mean for us in serving at-promise students? It means that we must make knowledge acquisition a top priority. Steps might include the following:

- Formally mapping out the names, dates, place, people, and ideas that are part of your curricula – The Core Knowledge Foundation offers a variety of free resources to assist with this.

- Restoring any instructional time cut from social studies and science

- Ensuring that students are read to daily, ideally from materials written about two grade-levels ahead of their tested reading level, which is an idea way to build vocabulary and, if the reading selection is non-fiction, knowledge.

To learn more about the role of knowledge in reading comprehension, consult the following resources available in the reference list that follows.

References

Fogarty, R., Kerns, G., & Pete, B. (2020) Literacy Reframed: How a Focus on Decoding, Vocabulary, and Background Knowledge Improves Reading Comprehension. Solution Tree.

Hirsch, E. D. (2016). Why Knowledge Matters: Rescuing Our Children from Failed Educational Theories. Harvard Education Press.

Hirsch, E. D. (2018). Cultural Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know. Vintage.

Pimentel, S. (2018), Why Doesn’t Every Teacher Know the Research on Reading Instruction? Education Week. Retrieved from https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/opinion-why-doesnt-every-teacher-know-the-research-on-reading-instruction/2018/10

Schmoker, M (2018). Focus: Elevating the Essentials to Radically Improve Student Learning. ASCD 2nd Edition.

Tyner, A, & Karourek (2020). Social Studies Instruction and Reading Comprehension: Evidence from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study. Fordham Institute. Retrieved from https://fordhaminstitute.org/national/resources/social-studies-instruction-and-reading-comprehension.

Willingham, D. & Lovette, G. (2014). Can Reading Comprehension be Taught? Teachers College Record. Retrieved from http://www.danielwillingham.com/uploads/5/0/0/7/5007325/willingham&lovette_2014_can_reading_comprehension_be_taught_.pdf.

Willingham, D. (2017). The Reading Mind: A Cognitive Approach to Understanding How the Mind Reads. Jossey-Bass.