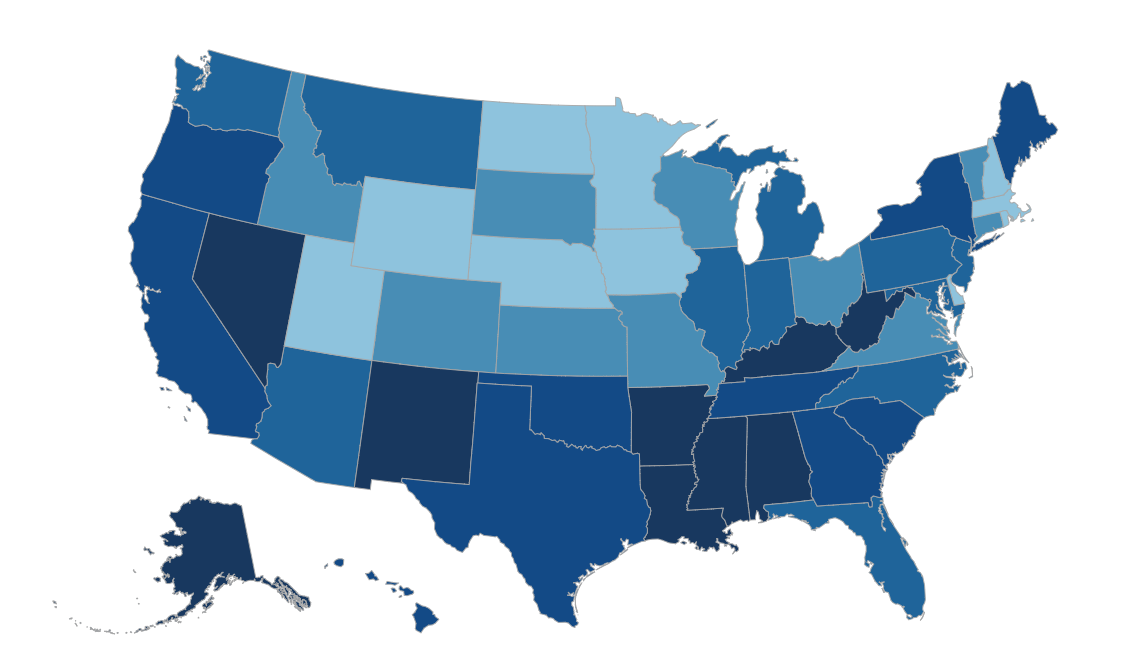

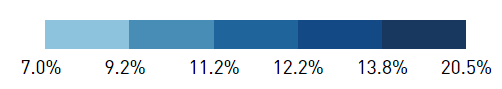

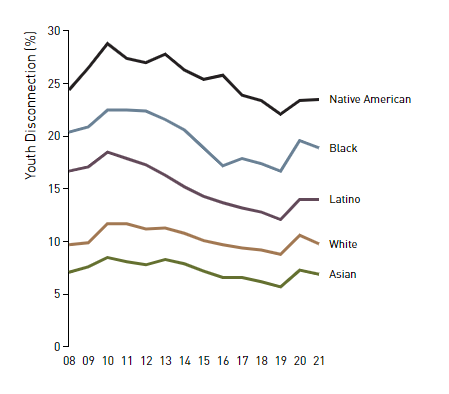

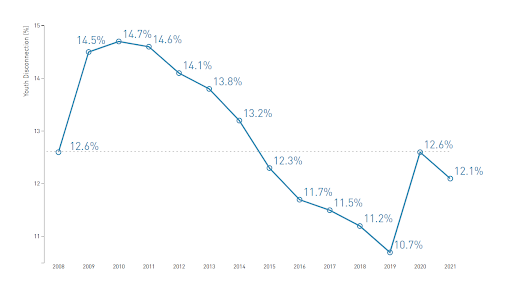

One of the goals of our nation’s public schools is to prepare students to enter the workforce. State and federal expenditures on schooling have been significant over time. In 2022, public K-12 expenditures were approximately $795 billion and in that year the nation’s graduation rate in 2022 was roughly 85%. The students who did not complete high school and did not enter the workforce are commonly known as Disconnected Youth or Opportunity Youth - young people between the ages of 16 and 24 who are not in school and not working. Without a high school diploma and few career options, most of these youth survive on the margins of society, stuck in low-wage jobs with no clear path towards a career that will pay a livable wage and put their lives on a more promising trajectory. Collectively, we all pay a price in terms of a diminished workforce and greater demands on the nation’s social services.

A Golden Opportunity

In 2021 and 2022, the Biden-Harris administration passed three major pieces of legislation that has set forth investments of more than $2.3 trillion to modernize our nation’s infrastructure in transportation, climate, energy, environmental, and digital telecommunications. To be certain, the United States is at the beginning of a government-supported building-boom, and these investments in our workforce to do this critical work represent a once-in-a-generation opportunity to create access to good jobs for underrepresented workers, including women and communities of color. Moreover, the policies and programs to be developed under this legislation constitute an important opportunity to remove barriers to participation for Opportunity Youth while creating accessible career pathways to livable-wage jobs, so that they may reach their fullest potential.

Although these forthcoming employment opportunities funded by this legislation are commonly referred to as infrastructure jobs, the career pathways that will emerge and expand will not be exclusively for builders and construction workers. Driven by the rebuilding of our infrastructure, there are dozens of other occupations that will be created in various fields including cybersecurity manufacturing, electric vehicle production - and jobs that have not yet been created - over the coming years.

When compared to all jobs nationally, these jobs will pay 30% more to lower-income workers and individuals just starting their careers with lower formal educational barriers to entry. This will create millions of new jobs annually wherever new infrastructure or manufacturing facilities are built (Zhavoronkova & Walter, 2023), representing a tremendous opportunity to lift millions of Opportunity Youth out of poverty and change their life trajectories (Zhavaronkova, 2022). This will be no easy feat, however.

| Most infrastructure workers (53.8%) have a high school diploma or less, but they achieve higher wages than in other industries and grow their careers through on-the-job training. The share of infrastructure workers with a high school diploma or less contrasts sharply with the share of workers across all occupations nationally, 31.6% of whom have a high school diploma or less. Meanwhile, 86.8% of infrastructure workers need some level of on-the job training, compared to 62.6% of workers across all occupations nationally. Through apprenticeships and other work-based learning, they develop knowledge in many common categories, such as public safety and security or engineering and technology—highlighting the need for more collaborative approaches among employers and educators (Kane, 2022) |

To ensure Opportunity Youth have access to livable-wage jobs, it is critical that policymakers, educators, and workforce leaders give thoughtful consideration to policy solutions that will remove long existing barriers to youth re-engagement, while creating broad and accessible pathways to the high-quality infrastructure jobs afforded by our nation’s forthcoming building-boom.

Five Policy Recommendations to Ensure Equity and Access for Opportunity Youth

Reduce barriers to entering the infrastructure workforce by providing supportive services to Opportunity Youth. The costs of training for career pathway jobs go beyond tuition or training fees. Expenses like books and supplies, equipment, transportation, and childcare present substantial barriers for Opportunity Youth. To remove these barriers, policymakers can invest in economic support for basic services for disadvantaged youth, and make the pursuit of viable career pathways possible. Policy leaders can also make debt-free financial aid more readily available for short-term training programs that meet quality assurance standards and are offered by public community and technical colleges (DeRenzis, 2022)

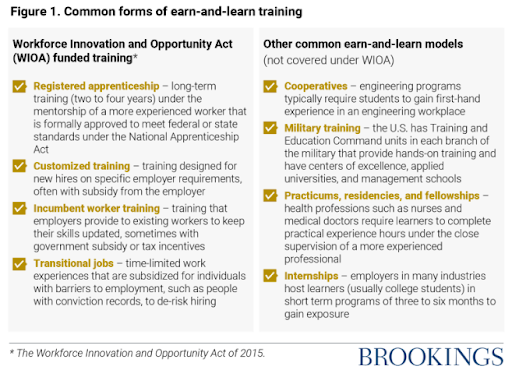

Expand and ensure access to earn-and-learn programs for Opportunity Youth such as pre-apprenticeships, apprenticeships, internships and other work-based learning programs that lead to certifications. Earn-and-learn pathways combine academic education with work experience and—if designed intelligently—provide a paid route to a college degree and lifelong learning rather than a separate and unequal track away from it. Work-based learning helps students and prospective workers develop and apply new requisite skills and provides them with experience to qualify for entry-level opportunities across the industry. Work-based learning programs help students and prospective workers develop and apply new skills while acquiring the experience and requisite skills to qualify for entry-level job opportunities in the industry. A registered apprenticeship combines classroom instruction with paid on-the-job training. Certificate programs allow earlier opportunities for individuals to receive a credential and move into skilled work, which can make college more economically feasible for low-income students. Stackable credentials also provide more structured education and credentialing in some fields that have traditionally had limited opportunities for upskilling and career building. (Goger, 2020, Daugherty, 2023, Zhavoronkova & Walter, 2023).

Reduce barriers to workforce development opportunities and CTE program completion for Opportunity Youth. Workforce development programs should specifically address the more than 5 million Opportunity Youth across the nation who are neither in school or gainfully employed. Programs to be developed should have specified on-ramps to enroll this population, as well as a set aside of outreach funds to be incorporated in all programming. The federal Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) provides limited funding targeting out-of-school young adults; however, the documentation and eligibility barriers often result in under-enrollment and under-utilization of the system. Young adults who are out of the educational system should be co-enrolled in appropriate school settings and enrolled in Workforce Innovation Opportunity Act (WIOA) funded programs. This can be achieved by streamlining access and support for both programs.

Create incentives and foster collaboration among local agencies serving Opportunity Youth at the local delivery level for integrating and aligning local, state, and federal funding streams. Models like the federal Performance Partnership Pilot (P3) encourage the integration and braiding of federal, state, and local funding streams, and programmatic waivers to deliver comprehensive services to Opportunity Youth populations. Using the established performance partnership model, P3 aims to facilitate improvements in how local youth-serving agencies work together through supporting changes in their government structures, communication practices, and data-sharing approaches to better meet the needs of Opportunity Youth. The model offers state and local agencies the flexibility to integrate separate funding sources and to streamline the administrative requirements of the grants. In exchange, participating agencies face heightened accountability for achieving negotiated performance goals.

Collect data and report on jobs outcomes of federal infrastructure spending with attention to Opportunity Youth. To track the progress of efforts toward building an inclusive infrastructure workforce, all workforce development programs should include relevant data regarding Opportunity Youth. This will help ensure equitable gains for this marginalized population through greater accountability.

What It Will Take

Ensuring that new programs developed to rebuild our infrastructure provide equitable access for Opportunity Youth will require coordination among key actors including, but not limited to, employers, educational institutions, workforce development boards, community-based organizations, and labor groups. Developing clear and effective career pathways will require creating new sector partnerships, expanding work-based learning programs, and more intentional outreach for Opportunity Youth. By removing economic barriers and creating equitable access to educational opportunities and viable career pathways, key actors can drive strategic investments in a 21st century workforce that guarantees access to well-paying jobs for disconnected workers, in general, and Opportunity Youth in particular. In this way, these historic investments can lift millions of young people out of poverty and advance equity and economic justice for families that have long-lived on the margins of society and put them on a path to the American middle class.

Recently passed federal legislation stands as an exceptional opportunity for policymakers, educators, workforce leaders and industry executives to invest in Opportunity Youth so that they may break free from cycles of poverty and build brighter, more fulfilling lives for themselves and their families. Through these investments we can meet our nation’s demands for resilient, sustainable, infrastructure, and simultaneously redesign our educational, training and workforce systems to include on-ramps for marginalized youth to enter the workforce. This will only happen, however, through strategic policymaking that thoughtfully leverages these investments to effectively serve the equity goals of this historic legislation.

These investments, guided by our commitment to improving outcomes for marginalized youth, will provide them with career-connected learning experiences that help build job skills, acquire human capital and gain agency over their lives.

Dr. Terrance Mims serves as the Superintendent of SIATech High Schools and Acting Executive Director of RAPSA. He has 25 years of leadership experience in secondary schools and is dedicated to creating more equitable school systems for all students. Dr. Mims has served as an adjunct professor at the University of Washington and at Antioch University, Seattle in Educational Leadership. He holds a bachelor’s degree in Public Administration from San Diego State University as well as a master’s and doctorate degree in Educational Leadership and Policy Studies from the University of Washington.

Sources / Further Reading

COYN and New Ways to Work. Expanding Workforce and Career Development Pathways for Opportunity Youth. Bay Area Transition-Age Youth Workforce Initiative, California Opportunity Youth Network, 2022. Link: https://jbay.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/COYN-Action-Guide_Digital73.pdf

Daugherty, Lindsay. “Stacking Certificates and Degrees: The Lessons We’ve Learned So Far.” Insider Higher Ed., August 3, 2023. Link: https://www.insidehighered.com/opinion/blogs/beyond-transfer/2023/08/03/stacking-certificates-and-degrees-lessons-learned-so-far

DeRenzis, Brooke. As the infrastructure bill is implemented, NSC pushes training for the next generation of infrastructure workers. Washington D.C.: National Skills Coalition, 2022. Link: https://nationalskillscoalition.org/blog/apprenticeship/as-the-infrastructure-bill-is-implemented-nsc-pushes-for-policies-that-train-the-next-generation-of-infrastructure-workers/

Groger, Annelies. Desegregating work and learning through ‘earn-and-learn’ models. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institute, 2020. Link: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/desegregating-work-and-learning/

Kane, Joseph W. Commentary: The incredible shrinking infrastructure workforce — and what to do about it. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institute, 2023. Link: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-incredible-shrinking-infrastructure-workforce-and-what-to-do-about-it/

Kane, Joseph W. Seizing The U.S. Infrastructure Opportunity: Investing In Current and Future Workers. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institute, 2022. Link: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/InfraJobsUpdate_final.pdf

Kane, Joseph W. and Robert Puentes. The Enormous Wage Potential of Infrastructure Jobs. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institute, 2014. Link: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-enormous-wage-potential-of-infrastructure-jobs/

Kane, Joseph W. and Adie Tomer. Infrastructure Skills: Knowledge, Tools, and Training To Increase Opportunity. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institute, 2016. Link: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/infrastructure-skills-knowledge-tools-and-training-to-increase-opportunity/

Lewis, Kristen. Ensuring an Equitable Recovery: Addressing Covid-19’s Impact on Education. New York: Measure of America, Social Science Research Council, 2023. Link: https://measureofamerica.org/youth-disconnection-2023

PBS News Hour. “Biden bill includes boost for union-made electric vehicles.” Nov. 11, 2021. Link: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/economy/biden-bill-includes-boost-for-union-made-electric-vehicles

Tomer, Adie, Joseph Kane, and Caroline George. Rebuild with Purpose: An Affirmative Vision for 21st Century American Infrastructure. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institute, 2021. Links: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/american-infrastructure-vision/ and https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/20210413_BrookingsMetro_American-Infrastructure-Vision_Report.pdf

U.S. Department of Education Office of Career, Technical, and Adult Education. Overview: Unlocking Career Success. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, 2024. Link: https://cte.ed.gov/unlocking-career-success/about

U.S. Department of Labor. What is a Registered Apprenticeship Program? Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Labor, 2024. https://www.apprenticeship.gov/employers/registered-apprenticeship-program

Walter, Karla, and Mike Williams. 3 Major Wins for Workers in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Package. Washington D.C.: Center for American Progress, 2021. Link: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/3-major-wins-for-workers-in-the-bipartisan-infrastructure-package/

Youth Employment Funders Group. What Works in Soft Skills Development for Youth Employment? A Donors' Perspective. Mastercard Foundation, 2018. Link: https://mastercardfdn.org/research/soft-skills-youth-employment/

Zhavoronkova, Marina. Meeting the Moment: Equity and Job Quality in the Public Workforce Development System. Washington D.C.: Center for American Progress, 2022. Link: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/meeting-the-moment-equity-and-job-quality-in-the-public-workforce-development-system/

Zhavoronkova, Marina, and Rose Khattar. Infrastructure Bill Must Create Pathways for Women To Enter Construction Trades. Washington D.C.: Center for American Progress, 2021. Link: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/infrastructure-bill-must-create-pathways-women-enter-construction-trades/

Zhavoronkova, Marina, and Karla Walter. How To Support Good Jobs and Workforce Equity on Federal Infrastructure Projects. Washington D.C.: Center for American Progress, 2023. Link: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/how-to-support-good-jobs-and-workforce-equity-on-federal-infrastructure-projects/